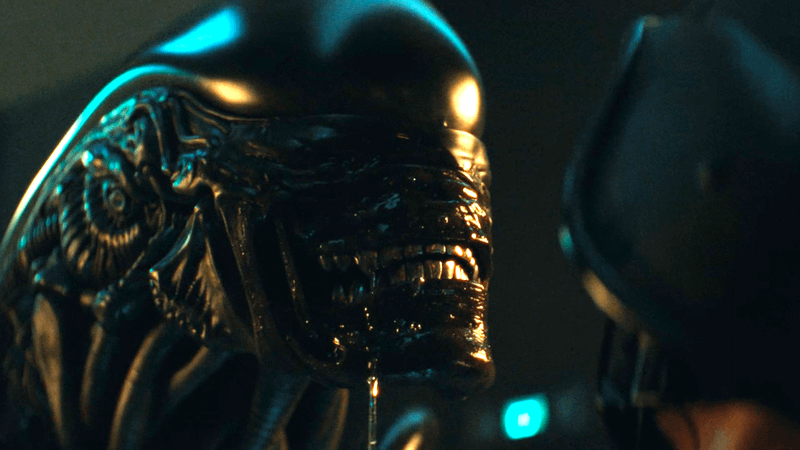

Noah Hawley’s new Alien: Earth series delivers a lived-in world that feels weathered, dangerous, and oddly familiar. Featuring a mix of practical creature work, tactile production design, modern CGI elements, and an engaging cast of characters, it’s an earnest and fresh expansion upon the foundational text Ridley Scott laid down nearly 50 years ago. But perhaps most important to why Alien: Earth is a new journey worth taking is that it never forgets the layers of complex elements that have made the franchise so iconic and enduringly chilling.

Set in 2120, two years before the original Alien, Alien: Earth follows the catastrophic crash of the research vessel Maginot and the terrifying lifeforms it brings to Earth, forcing humans, synthetics, and hybrids to confront new threats. Starring Sydney Chandler (Don’t Worry Darling), Alex Lawther (Andor), Timothy Olyphant (Justified), Essie Davis (The Babadook), and Babou Ceesay (Rogue One), this new installment in the franchise holds its horror close. It’s the sort of show that pulls you into its orbit, and where the tiniest detail can flip a scene from demure to deadly.

This conscious balance of nostalgia and innovation is why Jeff Russo was the exact composer this project needed. An Emmy-winning collaborator of Hawley’s (and founding member of the band Tonic) with a résumé including Fargo, Legion, Ripley (no, not that Ripley), and multiple Star Trek projects, Russo’s approach for Alien: Earth leans less toward quotation and more toward conversation with the franchise. Sure, there are nods to the composers who paved the Alien way, but the final result is something altogether new that boldly goes where no Alien score has gone before.

Dread Central recently spoke with Russo about entering this sci-fi hallowed ground. Read on for a conversation about restraint versus homage, the unique instruments that helped define the Alien: Earth sound, and how voices can be used to reintroduce the human in an increasingly inhuman world.

Dread Central: Alien: Earth is here, it’s out, and I, for one, have really been enjoying it. It must feel so wild finally having this out there and seeing everyone’s reactions.

Jeff Russo: Yeah, thank you! I wrote the first piece of music for this about five years ago, so it’s been a long time. And we’ve taken a lot of care and a lot of time to make sure that everything we do is what we think is the right thing. And lots of things I did two and a half, three years ago, changed pretty dramatically. But the germ of the idea that I had, that Noah had, about the way the show was gonna be was when we first started back in 2021, late 2020 even. I think Noah started talking about it in 2019. Things like this, they take a long time.

DC: Oh, I can’t even imagine. This show strikes a balance between the franchise’s rich history, while also exploring a lot of new narrative territory. What were some of the initial conversations like with Noah about the show’s musical direction? As it could have gone so many different ways.

JR: Yeah, it could have. Noah and I both agree that the first movie is the greatest horror movie of all time, and the second movie is the greatest action movie of all time. So it was, how do we merge those two ideas, while injecting a unique voice; something new, something identifiable, that is uniquely ours. For the way we’re telling this story, how do we do all those things and not have it feel like one mishmash, right? But also to still have it feel like what you think Alien sounds like. So that was the original conversation.

And I think the most important thing that we talk about again and again when adapting material that is beloved by fans, the idea is not to copy. The idea is not to try to do what they did, but to study. To figure out what that was making the viewer feel. And figuring out what I can do to make the viewer feel some of those same things without it feeling like just a carbon copy, you know what I mean?

I didn’t want to sound like I was trying to do my version of Jerry Goldsmith. Or my version of James Horner. Or my version of Elliot Goldenthal, or any of the many composers. I didn’t want to do that. And Noah didn’t want to try to make a Ridley Scott film. He didn’t want to make a James Cameron film of a Fincher film. So, figuring all that out, that’s been the conversation since the very beginning, and we continue to have it.

I saw Noah last night. I went to Austin and we screened Episode 5 in a movie theater, which was incredible. Definitely how we wish people could see it, because this particular episode, it was meant as an homage to that first film. And we talked about exactly what I’m telling you now. We continue to have these conversations, and if we end up doing a Season 2, I’m sure we’ll continue those conversations as it relates to continuing on in the story.

DC: One of my favorite things about the Alien franchise is the tactility and the sounds that result from that. I’m thinking about Mother and the ship sounds in particular. And that line between sound design and score often blurs in such a fantastic way. How did you, or did you, collaborate with the show’s sound designers? Are you involved in that process at all?

JR: I am and I’m not. When the sound mix happens, choices are made. But there’s definitely a sound design aspect to the score. I usually deliver lots of different stems, so if there needs to be music, but the sound design needs to happen, you could take the stem of sound design material in the score, and you can turn it down, or you can mute it. So you can have both coming together.

The sound design team and my team, we all talk about how we’re going to treat something and what we’re going to do. And I talk with the editors, and I talk with Noah, and we discuss what the important sound piece is in any given scene. A lot of that also falls to my music editor, who will sometimes have to edit music around sound design. And then there’s the sound design editor, who would then maybe carve out sound design for the score. There’s really no one way about it. There are many different possibilities, and we go through all of them.

DC: Movies are seriously magic. It takes a bazillion people to pull them off, and that’s fascinating.

JR: It’s so interesting to watch films or shows where you watch the end credits of television that require the level of VFX that our show has, and the pages and pages of names that go by with how many VFX vendors there are. There are so many people all doing it, because they’re doing like, six seconds. And when you’re talking about as many hours as we have, there’s a lot of work to be done, so you need a lot of people.

DC: Part of this show that I really wasn’t expecting, but have been loving, is this sci-fi fantasy-tinged world that we get through Wendy, her brother, and The Lost Boys. Can you walk us through your approach to their story and this element of the series?

JR: The emotional content of our telling, our story, is certainly something that’s a little new to this franchise, right? The character connections. It’s not just about the people on the ship running around getting their heads cut off by xenomorphs and/or other varying alien life forms.

So, in that, we talk about how music is the heart of a story. I can underscore real emotion between characters, and that’s a really important aspect to music that can be used, not just to elicit fear, not just to elicit tension and the unknown, but to really dive into character bonding, character connection. And I’m very much in the frame of mind of never wanting to score what characters are doing, but really wanting to score what characters are feeling. That’s a very Jerry Goldsmith-ism, and I learned that very early on in telling narrative stories for film, TV, and any kind of media.

So when faced with the script that Noah sent me early on, we talked about wanting a theme for the siblings, and I wrote that piece of music called “Siblings.” It comes up in the series on a number of occasions, but most notably in Episode 2 when Hermit finally acknowledges, or finally starts to believe, that Wendy actually is his sister. They hug, and there’s this moment.

It’s interesting, because I’m an only child. I never experienced that, but I’ve experienced it from afar. So I did the best I could to write a piece of music that felt genuine to that moment. I wrote this big piece of music, knowing that it was going to be in that particular scene; this four-minute piece of music, I know that only 20 seconds of it is going to get used in this moment. So I sent it to Noah, and Noah was like, “Wow, this is great!” It really worked in terms of what he thought in his head.

Then the scene got shot, things got moved around, and we spent days figuring out exactly when to begin the cue, when to begin the piece of music. Is it on the realization? Is it on the hug? Is it a moment before the hug? Is it the hug? We went back and forth. Finally, we came upon where we ended up. It is only like a 15-second or 20-second piece of that there, but that cue actually does end up rearing its head in other spots in this series.

But in that moment, a small part of it gets used, and it’s interesting to see how powerful even a small part of that can be against the right picture. Feeling those feelings in that moment was very meaningful for me because it was like I got to experience that feeling through Noah’s storytelling. It was pretty intense.

DC: I love that, as that’s part of the real beauty of movies, right? Getting to feel difficult, and beautiful things, and feel catharsis, but from a safe place.

JR: That’s exactly why a lot of our show is lulling the audience into a feeling of safety and then…it’s not safe.

DC: Yeah! OK, so you mentioned the other creatures that pop up in this show. We get our beloved xenomorphs, of course, but we also get some other really creepy creatures. And every episode, it just keeps getting worse.

JR: [Laughs] Yeah, poor sheep.

DC: How did you approach scoring these additional little nasties and bringing their new sonic identity to life?

JR: When talking about this idea with Noah, he was like, “The one thing we can’t do is give people the experience of seeing the xenomorph for the first time again.” Once you’ve seen it, it’s over. So the only way to bring back that feeling would be to have new creatures that we’ve never had. In any of these Alien films, it’s always only been the xenomorph. Which, by the way, is the most stunning design ever.

So, I needed to think about it from the perspective of, “Okay. We get to have this moment again.” I want people to think they’re going to see something that they have seen before, and then be really either grossed out, or scared, or whatever. So the way to do that would be to treat it in a way that you would expect. You get to have this creature feature style music that might make you think, “Oh, I know what’s coming.” But really, you don’t.

DC: One thing I love about horror and sci-fi music is the room for composers like yourself to get weird with instrumentation or techniques. Did you use any bespoke instruments or extended techniques to add that extra something special?

JR: Yeah, as a matter of fact, there’s this instrument that I had made. It’s called a bassdesmophone. It’s a unique instrument that is metal with two strings. It has so many different possibilities, and it gets used in Episode 5 on every piece of music, basically.

I can bow it, I can hit it, I can tap on it. It’s used as a percussion instrument and a melodic instrument, and a tonal instrument. It’s the sound of the Alien: Earth score that I was looking for at the very beginning. Because, typically with a new project, I’m always looking for something different, something new, something that’s going to be unique.

That’s usually a mix of some sort of sound and some melodic instrument, melodic element or motif element. And this particular instrument provided me all of the things I needed. I needed something to sound eerie, emotional., and intense, and that did all three of those things, so it was perfect.

DC: I want to talk to you about the idea of space, but not like outer space. I’m fascinated by how a note’s decay and the room it lives in, and feeling the physical performance of an instrument, the impact that can have. How do you think about capturing room tone and the authenticity of instruments when you record? Who are these conversations happening with?

JR: I talk about the sound of the score with my engineer. I don’t typically write the score with the sound of the performance in mind yet. Because a lot of that I like to leave some room for. I want it to become something. I want it to have its own life.

And, I conduct the orchestra as well. So when I’m working with the orchestra, it’s interesting, because the score becomes something. More than you think it was going to be. The score becomes something more when you insert live musicians.

The human element also creates something that’s unknown, right? I can sit with my computer and write a piece of music and be very meticulous about things, where this is going to play, where that’s going to play. But when you put the music in the hands of musicians and you’re in a room, something happens, something changes. You end up with something that you didn’t expect. So, I don’t typically account for that when I’m writing, but I do think about it because I know it’s going to take another step. That’s the unknown step, though, and that’s one of the more fun things about it.

For me, one of the best parts is to get up in front of the orchestra and conduct them, talk to them, collaborate with them in how something is going to sound, in the way the violin section might play a specific passage, or like, how hard the horn players are playing. I can mock it up with a sample, but there’s nothing really that does specific things that individual players can do. When you get four people, or eight people, or 20 people, or in this case, it was closer to 70 people in a room, things start to sound different.

That’s part of the reason why I’m constantly trying to hammer home to producers and production companies that it’s very important to have live musicians involved in a score, or a score that you want to sound like that. Obviously, there are scores that can be completely electronic, and they’re meant to sound cold and devoid of emotion and feeling. And those get made in a different way. But when you’re talking about wanting to ground something, or wanting to inject emotion into a piece, the human element is impossible to replace with something else.

DC: It makes sense, because this is the first Alien movie-type project that’s actually happening on Earth, and that groundedness is essential. Outside of the Alien vs. Predator movies, anyway, but that’s a different tangent.

JR: I don’t count that as an Alien movie.

DC: I know, right? They feel much more like Predator movies to me.

But to follow that up, is that resistance to hiring live performers something you’ve encountered throughout your career? Or is that becoming more of a thing where you have to justify or explain that to producers?

JR: Cost-cutting, it’s always a thing. It’s a thing I’ve been dealing with my entire career. Trying to get people to spend more money to make something better is difficult when they’re like, “Well, you can just do it on your computer! It’ll sound good!” And the answer or the response to that is, “Yeah, I guess you’re right. It can be done that way, but it does not sound as good as it could.”

But the fact is, some people just don’t care, and that’s the difference. When you really care, you do the best that you absolutely can. And the people who are the people with their hands on the purse strings, they don’t really care as much, I think, about the creative. They’re thinking of the creative in terms of its commerce.

And I’m not saying everybody’s like that, because they’re not. I’ve had producers fight for wanting to use real players and humans. It’s not a broad statement; it’s just an overarching idea that people are trying to merge art and commerce. How do we find the medium? Because they’re trying to make money.

Obviously, we made Alien: Earth, and yes, the artists make it because we want to make art. And yes, we’re very glad people pay us to do this because people will enjoy it, right? And people pay to enjoy stuff, right? So, it’s a very fine line trying to get people to do more. And it’s important to me because I enjoy it. I love the act of making music with other humans.

DC: You integrate some gorgeous vocals into this score, too, which definitely adds to that human, grounding element.

JR: It’s meant to be disconcerting. The sound of human voices, I did that specifically to humanize the score in a moment where you are inundated with non-humans; with aliens, with synths, with hybrids. It’s like, where’s the human element there?

And a lot of the humans in our show are the bad guys, right? Not all of them, but a lot of them are. And it’s interesting, the humans that are walking the line. Dame Sylvia (Essie Davis), for instance, walks that line between wanting to think that she’s one of the good ones. Wanting to, and yet still edging towards the bad guy by being a part of this situation where they’ve taken children and killed them.

Like, these children were killed! Let’s not joke around. These children were murdered, right? They may have been dying, but that’s not relevant, right? Fuck! [Laughs] So, trying to find humanity amongst humans that are really acting like animals. That’s the important part of trying to shed light on the humanity of the situation.

DC: So, you have a unique distinction that I can’t not ask you about. You’ve worked on two of THE heavyweights of sci-fi — Star Trek, and now Alien. But also, Star Trek and Alien both feature scores by Jerry Goldsmith and James Horner.

JR: I’m so glad that you caught this. I find it interesting that I have now had to step into the shoes that they both filled, successively. It was always Jerry Goldsmith, and then James Horner. They both did something very unique for each of those things. The score for Alien is definitely very different than the score for Aliens. And the score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture is definitely a lot different than Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

And what’s so very interesting to me is if you look at each one of those franchises as a whole, and you were to ask me, “What are your favorites?” I would always say Goldsmith and Horner. That’s not to say that Elliot Goldenthal’s Alien 3 score wasn’t great. It’s really interesting, and I actually met Mr. Goldenthal and was very excited to meet him! What an incredible moment I had talking to him about music. And there were a number of composers in later Star Treks that were great. But when you talk about the quintessential ones, it’s always Goldsmith-Horner.

Yeah, it’s interesting that I have now done that twice, with two very different properties. And by the way, totally different styles of music. Totally different ways scores are utilized and what they’re doing. Yet the thread continues.

But for me, it’s terrifying. It’s terrifying. It was terrifying when I first walked into Star Trek. Probably even more terrifying walking into Alien. For me, it’s funny because the movie Aliens, was the first one that I actually got to see. I was too young to see Alien in the theaters. Arguably too young to see Aliens in the theater as well, but I saw it in the theater and then went back to see Alien on VHS. I’m now officially dating myself, but I would say that Aliens had a profound effect on my love for film and my love for what music can do to films.

It was the first movie I had ever seen that I was literally on the edge of my seat, literally feeling my heart pound in my chest. I remember where I saw it, who I was with. I remember all of those things and feeling like I was breathing heavy in a movie. That had never happened to me before. That didn’t happen to me with Trek. I came to Trek later in my life. However, interestingly enough, the very first Trek I saw was The Wrath of Khan.

DC: Oh, interesting. Horner both times.

JR: Horner both times. And then I went back. But where I really came to be a huge fan of Trek was The Next Generation, right? That’s where it became something for me. My development as a musician was later when I became a Trek fan, then my development as a musician when I became an Alien fan.

When I saw Alien, music wasn’t something that I was really thinking about. I was playing guitar or whatever, but I was young. I was 14. So it wasn’t so important to me. But when I started getting into The Next Generation, music was already my world and my life. So it was interesting going into Trek from that perspective, and then reimagining Aliens from that same perspective was different.

DC: What a surreal aligning of the stars that you are now officially a part of this dual Goldsmith-Horner sci-fi score legacy.

JR: To even have ever imagined that my name would be uttered in the same sentence as those two titans of film music is very surprising to me. I never expected that. And, it’s terrifying. There’s a lot of history, and they went about writing music in a much different way than I go about writing music. But, oh boy, those scores are really incredible.

Alien: Earth is now streaming on Hulu. You can also stream Russo’s music for the film via Hollywood Records, available now on all major streaming platforms. A 2xLP vinyl release is also planned, with details to be announced soon.

https://ift.tt/vkmoYEg https://ift.tt/FYg9jfa

No comments:

Post a Comment